Little Writer in the Cramped Spare Bedroom

One of the canons of modern fiction is to keep a tight check on our impulses to overload scenes with block descriptions. Adjectives and adverbs should be tightly controlled, show, don’t tell, and so forth.

And then I read a great story written by someone who never picked up a writer’s manual, and who breaks ‘the rules’ left and right on the way to writing an American classic.

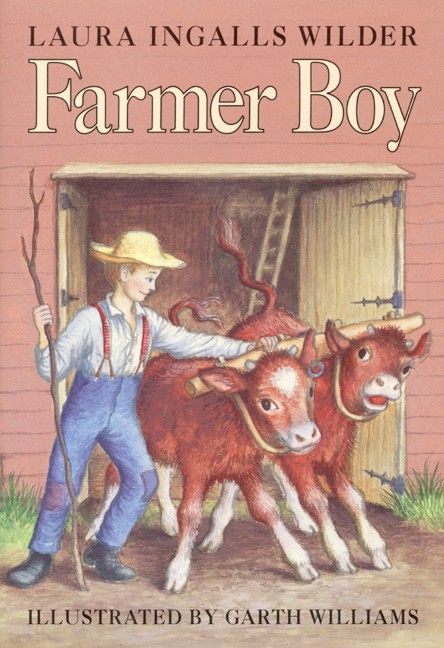

So it is with Laura Ingalls Wilder (left) and her LITTLE HOUSE books. Wilder, a product of the westward expansion of the late 19th century, was also a keen observer of human nature and a disappearing way of life—the family farm. She never knew her stories would end up becoming important histories, oral histories really, since her voice rings true on every page. She thought she was writing for children. When I was a girl, I never went more than a few months without reading one of her books. Now my daughter is discovering these stories, and I take great pleasure in reading them with her but through the lens of a writer as well as a reader.

What makes her books classics?

For me it’s that Wilder knew how to make the story come alive with sensory descriptions and universal emotions—almost primitive emotions. There’s nothing fancy about the way she lays down the layers. When Pa plays his fiddle and Laura feels cozy, I remember what it was like to feel safe knowing my parents guarded the dark. When she describes Laura’s rivalry with Nellie Olsen, not only do I remember my own jealousies, but I pity Nellie even as I hate her. Wilder also felt no compunction about dropping a big chunk of description in the middle of a scene. Thank god, because those chunks are where she preserved a way of life that will never return.

Here is an excerpt from her third novel, Farmer Boy. See if you wonder as I do where this little boy put all the food.

“Almanzo ate the sweet, mellow baked beans. He ate the bit of salt pork that melted like cream in his mouth. He ate mealy boiled potatoes, with brown ham-gravy. He bit deep into velvety bread spread with sleek butter, and he ate the crisp golden crust. He demolished a tall heap of pale mashed turnips and a hill of stewed yellow pumpkin. Then he sighed, and tucked his napkin deeper into the neckband of his red waist. And he ate plum preserves and strawberry jam, and grape jelly, and spiced watermelon-rind pickles.”

Hungry yet? I'll spare you the next paragraph, all about crisp apples and mellow pumpkin pie. Almanzo got to eat after a full afternoon at school, walking home two miles in the snow, then feeding the stock, churning butter for his mother, and chopping and gathering wood for the night’s fire. Then he had to wait while his father and the schoolteacher, Mr. Corse, finished talking politics. What kid hasn’t waited in agony for his parents to finish a boring discussion about affairs they never knew or cared about, all while delicious fragrant food sat steaming only inches away?

Universal emotions and sensory descriptions. See if you've got them in your current wip. Until then, write on.

In my next post, I'll talk about the techniques Wilder used to amp tension to the breaking point.

posted by Kathleen Bolton at

posted by Kathleen Bolton at

3 Comments:

I wore out two sets of these books when I was in third and fourth grade. I'm really looking forward to sharing these with my boys.

One of the stupidest things I've ever done was sell my tattered collection of Little House books at a garage sale when my mom informed me she was selling their house. Two years later I had my daughter...and I sorely regret it to this day. Thank gawd for reprints!

I had the fortune too of growing up in South Dakota and a mother who knew the value of field trips. We spend one vacation following the Ingalls family west, only we started in DeSmet and went east.

It was so awesome to see her house in DeSmet.

Post a Comment

<< Home